That day, eleven years ago, I wrote a song.

After the phone woke us, after the confusing early morning instructions to turn on the news, after watching the smoke and the fear and the death, I got in the car and drove to school. I worked evenings in those days and took classes at the community college during the day.

It was my second week in a songwriting class, and I was just a quiet imposter in the back row who could only play about four chords on the guitar and had only ever written one sappy love song. The instructor sat with heavy shoulders and tired eyes in a chair in front of the chalkboard. He held his guitar in his lap, though he never played it, just held it there like a security blanket between him and the cruel events of the morning. Maybe half the class was there that day, but some, those who had been in other classes all morning, had not heard the news yet. Our instructor told us quietly what he knew, what the news had been saying so far, and he sighed and hunched over his guitar and seemed suddenly much older than all of us.

And then he sent us home with an assignment: put your pain into a song. “This is what songwriters do,” he told us, “They give a voice to the cultural events of their day, they document the wars and the political upheavals, and they grieve and love and heal through music. So, go home and be songwriters.”

And that’s why, on September 11, 2001, I sat in a chair in the spare bedroom of our cheap Austin apartment and wrote a song that spoke of what I knew then, that spoke of people trapped in darkness like I believed people in the rubble of the towers were trapped. Waiting to be rescued, with families calling for them in the cloud of smoke, watching people walk the streets of New York covered in ash, pale like ghosts.

But when I share my September 11th story, I don’t tell anyone about writing that song. I tell them about the night before, when my husband and I had a picnic on a mild September evening. I tell them about the blanket we spread on the grass, about the real wicker-with-gingham-lining picnic basket we had back then, about the wine and the good cheese and the chocolate. That September 10th, as we were starting our third year of marriage, we sat together and marveled at the stars and at each other and at our unbelievable luck to be born into this country, of all places, during an era of extended peace and prosperity, of all times.

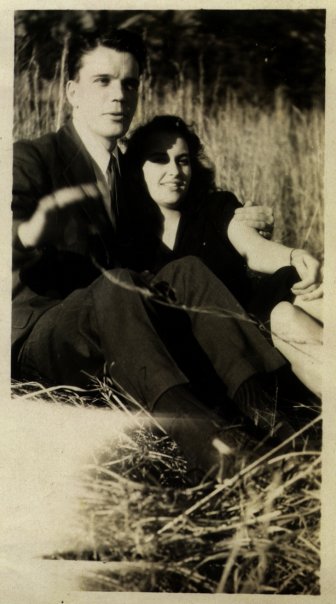

I remember we talked about our grandparents, how they always seemed thrown together in the romantic, terrifying flurry of war. To us, it seemed that in those old war-crazed years, people grabbed onto love like drowning fools, desperate for stability in the rocky waters of pre and post-war life. In a matter of months, or even weeks, people the same age we were that very night would meet, fall in love, marry at a courthouse or neighborhood church, and then kiss goodbye at a train station, not knowing if they would ever see each other again.

|

| Just another WWII romance - my grandparents. |

But not us, Sam and I said that night. We were part of a placid generation stumbling lazily into a new millennium with the confidence that we had time for anything, time for all of it. We were so far removed from the danger of war, it hardly seemed real. We went to bed that night wrapped in phrases of contentment, chocolate and red wine on our lips and starlight in our eyes.

Then, in the morning, we woke to smoke and debris, to sadness and terror. And it seemed we were jolted into another time, a past that we had spoken of the night before as if it were a quaint, almost fictional cultural experience we would never have ourselves. It was a wake-up call so vivid, it has driven the memory of that song I wrote right out of my mind. In the days that passed, then the years, it seemed more important that September 11th, 2001 be remembered as the moment that shattered our illusion of safety and stability than that it marked the day I wrote my second ever song.

Today, though, I woke thinking of that song because it is, for me, a poignant snapshot of not seeing the whole story. That day, as I pieced together amateur, melancholy lyrics, I wrote in the voice of an imaginary survivor trapped in the rubble of the collapsed towers. Someone on the news said that people would be found, lots of people clustered in stairwells and random air pockets, scared people waiting to be rescued. There were reunions waiting to be had in those mountains of brick, I believed that day, miracles to be seen as we sat at home watching it all unfold on TV.

Little did I know how naïve that hope would turn out to be. I only saw the part of the story I could bear to see, as inaccurate as that was, and every time I think of the song I wrote that day, I remember my naiveté. I remember what it feels like to look back and realize how little of the story you knew, what it feels like to view the past through the crystal clear vision of hindsight.

I need to remember today how little of the story I know, what skewed vision I have in the here-and-now. I need to remember it works both ways, that both good and bad seem sharper this close up, but that both begin to come into focus from a distance. This week I have a narrow focus and a weary heart, and I need to remember on this horrible anniversary that today, just as I did eleven years ago, I am only seeing one small part of a much larger picture. I need to remember today that no tragedy, no sadness, stands alone, that it is all part of a much bigger story whose print is written so large, we can hardly make out the letters from here.

Comments

Post a Comment